An untethering

Two poets and their collective grief...

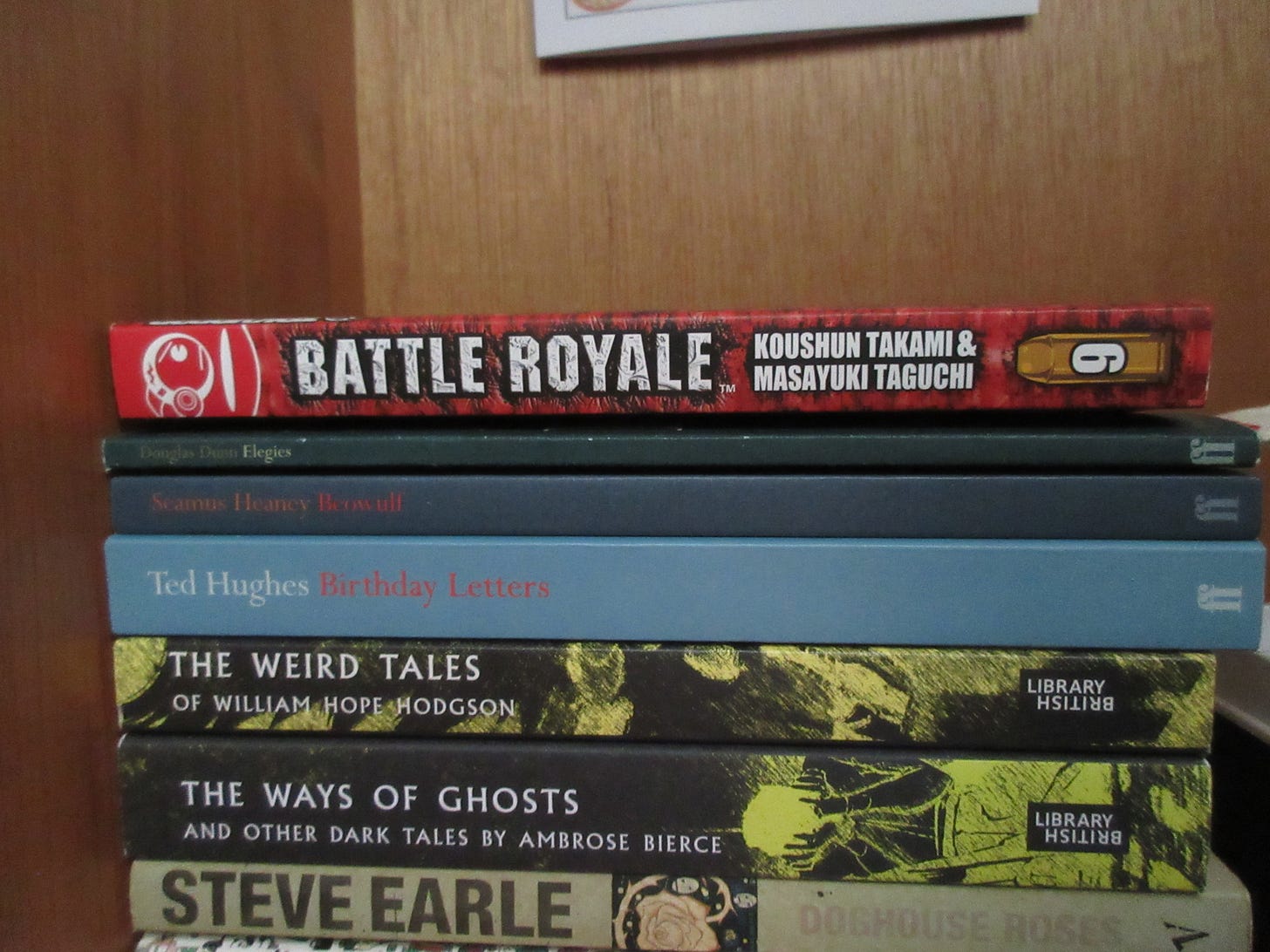

Sandwiched somewhere near the top of a short stack of books that I am in the process of reading is a slim, dark green volume of poetry, titled Elegies. As the name suggests, it is a record of grief; a collection of verses penned by Douglas Dunn following the death of his wife, Lesley Balfour Wallace Dunn, whose life was tragically cut short at a young age by cancer.

Elegies is apparently Dunn's best-known book. I had no idea of this, nor of its contents, prior to settling down to read it, decades after I purchased it on a whim in Foyles bookshop on Charing Cross Road; to give a sense of just how long ago, this was back when the Foyles was still in its original location. Before Elegies, I was reading Birthday Letters by Ted Hughes, which dwells upon the author's marriage to the poet, Sylvia Plath, who also died young, albeit by her own hand. It is entirely coincidental that I read these books one after the other. I wouldn't want to give the impression that I exclusively read anthologies of poetry eulogising dead spouses.

Hughes' poems are generally rather dense in terms of their symbolism and imagery. They come slowly into focus over many readings, stretched out over a number of days. There is an impression of a monolithic, godlike intellect at work in the background; one who is only too happy to drag the entrails of mythologies besides his own into his verses, if he believes that they will be of service to him. Another themed collection by Hughes, titled The River, is the kind of book that might conceivably form the basis of a revival in animism, were a copy to be raked ashes from the ashes of civilization in the aftermath of some apocalyptic event. It embodies that kind of opaque mysticism that one commonly finds in religious texts, where the salmon, their journey upriver to spawn, and the river itself are not distinct entities but all part of the same thing.

The poems in Elegies are lighter in their composition. I am not continually reaching for my disintegrating copy of Chambers Dictionary, or making scrawled notes to explore a reference the next time I am online. That is not to say that they are lesser works, but rather that they are the product of a different soul, working in a different style, to a different set of aesthetic parameters. When Birthday Letters was published, it was several decades removed from Plath. Of the two books, it is the more considered and it is certainly more stylised in its presentation. Elegies was published in 1985, four years after Lesley's death. The poems are Dunn's celebration of his departed wife and perhaps an attempt to give form to his grief while not being consumed by it. If Hughes and Dunn share common ground, then it is in their ability at picking engaging angles of approach. This talent for devising an intriguing framing device as a point of entry into a poem, is a common trait among those who excel in the art form.

As I progress through Elegies, I am learning a lot about Lesley. She was a young woman who embraced life; who reveled in art and food and culture; who had many friends who rallied around her after she fell ill, who prepared meals for her, and who climbed the two sets of thirteen stairs to her bed to sit with her. Dunn's grief is multifaceted, yet to distill into the singularity of acceptance. The light falls onto its surface in ways that cannot be anticipated. In Empty Wardrobes, he recalls, with a combination of guilt and regret how, while penniless if Paris, he put down a husbandly foot and denied his wife the opportunity to indulge in her love of dresses “as she browsed through hangers in the Lafayette”. What else could he have done, I wonder.

Unlike Hughes, whose poetry is mostly blank and labyrinthine in composition, and feels like it has manifested on the surface of old stones, or in the stumps of trees, or as a pattern of worn pebbles on the clear bed of a stream, Dunn's verses in Elegies are less abstract and make common use of rhyme. I congratulated myself on recognising the presence of a Shakespearean Sonnet. There are other rhyming schemes at work that I might be able to formally identity were I more academically minded.

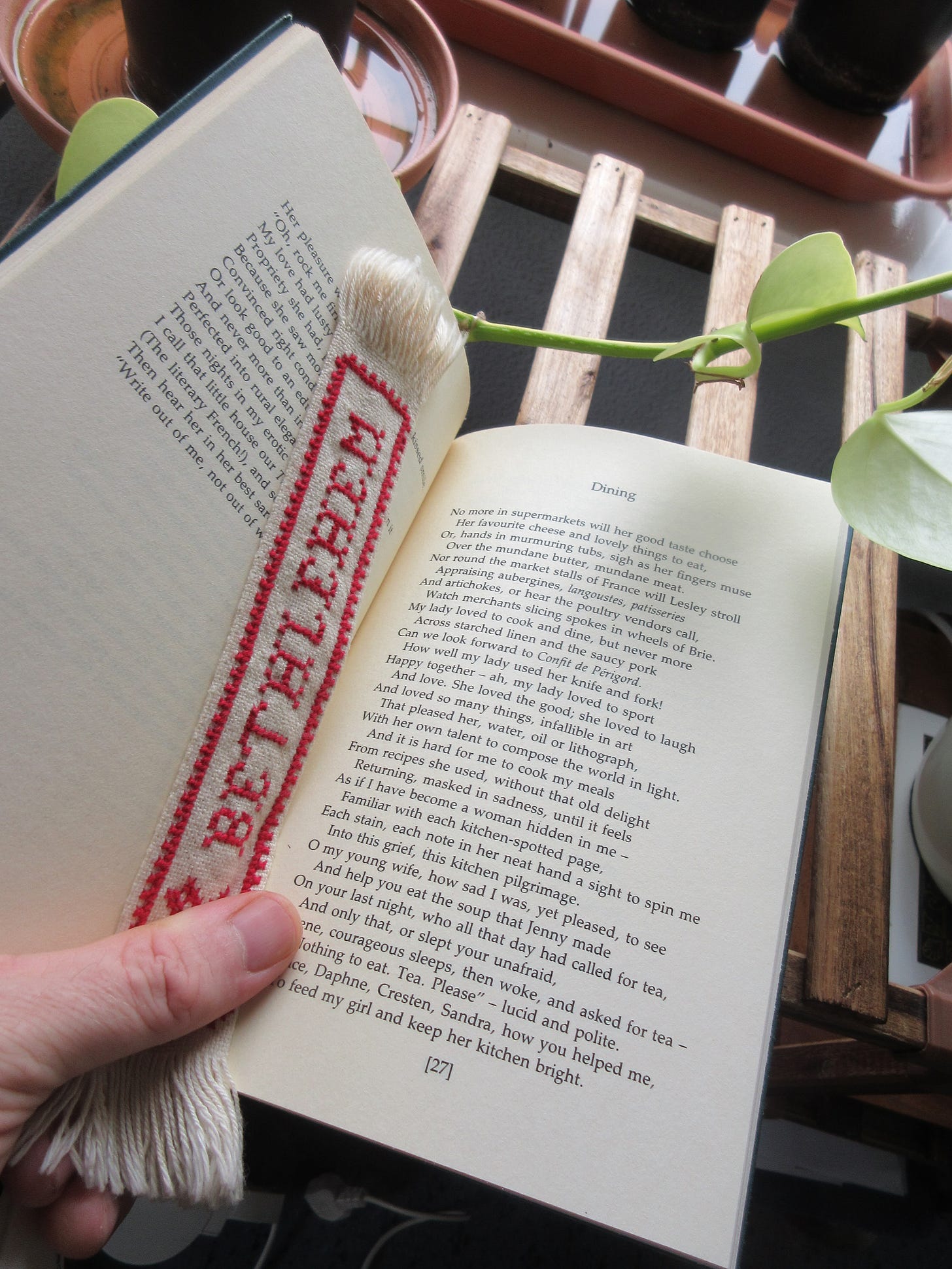

Having imposed these rigid structures upon his thoughts, he is more than happy to colour outside the lines; sometimes wildly outside the lines. His rhymes break in the middle of sentences. Reading these poems out loud, one must aim for a split-second timing between certain groups of words if one is to preserve the delicate balance between their rhythm and their meaning. Despite the recurrent ABAB structure of Dining, which I stumbled through for the first time yesterday, his thoughts are not so neatly parceled. The rhyming sentences flow not only between the lines but also between the quatrains. Attempting to fathom out how to read these poems is to become deeply involved in the minutiae of their composition and in their subject. I wonder whether this playful use of rhyme was an attempt by Dunn to communicate something of his wife's personality not only through words, but in the structure of the poem themselves.

He might take solace that, over forty years after the untimely passing of Lesley, her memory endures in his writing and comes vividly to life when these poems are read out loud by one who never knew her.